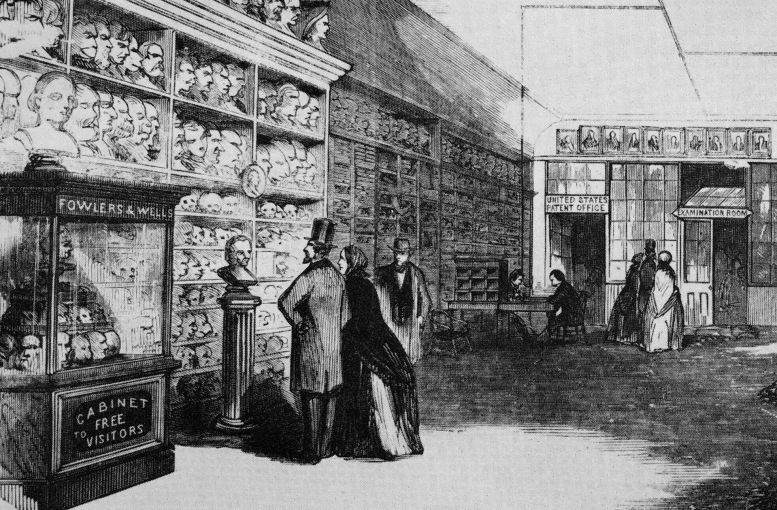

Fowler & Wells Phrenological Cabinet, New-York Illustrated News, 1860 (detail).

The Phrenologists: Participatory Knowledge in Antebellum America

“It is now my desire and determination, to afford every possible facility for the spread of Phrenology among all classes; and in my way, by cheap publications, private lectures, supplying societies with libraries and specimens, &c. &c…” So O.S. Fowler, America’s best-known phrenologist, described his mission in 1843.

For my dissertation, The Phrenologists: Participatory Knowledge in Antebellum America, I am researching the world of practical phrenologists and their audiences, with an emphasis on Fowlers & Wells, a major phrenological business firm. This project explores the relationship between science, commerce, and popular culture, using phrenology to recover a democratized mode of scientific exchange that became increasingly stigmatized over the course of the nineteenth century. Despite the attempts of anatomists and other critics to debunk phrenology – which became an iconic example of “pseudo-science” – it had a long-lived and major influence on American culture, in large part due to its radically consumer-oriented nature.

Proponents of phrenology believed that the shape of a person’s skull revealed their inner character. Americans favored “practical” phrenology, which bypassed theoretical discussions of the mind to provide individuals with specific, useful information about themselves. Phrenologists examined their customers’ cranial morphology, then offered customers insights into their own characters, charting the strengths or weaknesses of propensities like “alimentiveness” (appetite and digestion), “philoprogenitiveness” (love of family), and “constructiveness” (mechanical ingenuity). Phrenological character was mutable. By exercising specific organs of the brain, a person could develop desirable propensities. A customer might follow an oft-repeated phrenological motto — “Know Thyself” — or practice judging other peoples’ characters.

As genteel doctors and scientists began the attempt to professionalize their fields, phrenologists developed an alternate model for scientific work – a public-facing trade in ideas which I call “participatory knowledge.” Itinerant lecturers cultivated a conversational tone and invited audience participation. Publishers heralded the cheapness and simplicity of their books and pamphlets, boasting of their accessibility to “the million.” Cranial examiners offered customers practical advice regarding work, marriage, and health. The meaning of the science shifted in relation to its audience, as phrenologists constantly adapted their message to appeal to a wide range of people. Rather than limit their field to a professional elite, practical phrenologists encouraged customers to become phrenologists themselves. They made money by selling their science to as many people as possible, rendering the boundaries between consumer and producer porous.

By examining how and why phrenology spread from about 1830 to 1860, I illustrate a material process of self-making in the era of the idealized “self-made man.” Concentrated in the northeast, phrenologists helped people navigate a social (and often personal) rupture: the transition from agrarian culture to urbanized market society. They readied the psyche of the emerging middle class for the industrial age, reorganizing mental labor from a whole self to specialized organs, promoting introspection as a way to orient oneself to the market. Fowlers & Wells packaged their ideas as paper and plaster goods, commodities to be bought and sold. Practical phrenology demonstrates the production of market-oriented selfhood in the United States – and its export to destinations throughout the world.

To recover the workings of participatory knowledge, each chapter of my dissertation focuses on a different site of phrenological experience. The first chapter, on itinerant lecturing, explores the social background of phrenologists and how they identified their audiences. Often young men hailing from farm families, they sought alternatives to manual labor in an atmosphere of industrialization and economic instability, especially in the aftermath of the Panic of 1837. After teaching themselves phrenology from books, they went on the road, lecturing on the subject and performing public demonstrations of their ability to read character. Drawing from phrenologists’ journals and memoirs, plus the reactions of audiences found in diaries and newspapers, I explore how practical phrenologists fashioned their own credibility through egalitarian rhetoric and interactive performance methods.

The second chapter is an examination of phrenological publishing, with an emphasis on the periodicals, books, and busts produced by Fowlers & Wells, a firm based in New York City. The Fowlers harnessed the medium of cheap, industrial print to spread their ideas far and wide, encouraging phrenological autodidacticism. Their main publication, the American Phrenological Journal, offered “Home Truths for Home Consumption,” communicating phrenological “facts” in plain language and evolving in tandem with the tastes and opinions of its readers. Books like O.S. Fowler’s Illustrated Self-Instructor in Phrenology and Physiology, accompanied by plaster phrenological busts marked with the organs of the brain, served as tools to help customers become phrenologists themselves.

A third chapter considers the political ambiguity of phrenology, as represented by the Fowlers & Wells museum cabinet in New York City. The phrenologists displayed row upon row of “extraordinary heads” preserved in the form of plaster casts. These heads represented the full breadth of the social spectrum: pirates and poets, statesmen and slaves. The collection pertained to the controversies that consumed American discourse in the decades leading up to the Civil War, especially issues of race and politics. But in their effort to build a wide, national audience, Fowlers & Wells rarely expressed strong positions on these debates. They offered phrenological descriptions of the people represented in their cabinet, like Cinqué, leader of the Amistad rebellion, and Andrew Jackson. But they left the significance of these character readings up to the viewer, providing raw information that could be used to defend either side of issues like slavery or party politics. By design, the meaning of practical phrenology could shift, becoming whatever each audience member wanted it to be.

Finally, the fourth chapter is about phrenological character charts – the printed or hand-written descriptions of mental strengths and weaknesses provided by phrenologists to their customers. Through this product, phrenologists commodified the concept of self-knowledge. This chapter segues into a conclusion on phrenology in the Gilded Age; the decline of the science’s utopian, reform sensibility; and the waning of participatory knowledge as a business in an atmosphere of regulation and medical credentialing.

The cultural foment of the early-to-mid nineteenth century is in some ways analogous to our present digital age, as industrial print culture exploded, knowledge became more accessible, citizens questioned old hierarchies of expertise, and new forms of self-fashioning became available. Within this context, phrenologists emerged to sell an entertaining and accessible form of mental philosophy that elevated the individual – or at least, appeared to – amid the disjunctures of market capitalism.